What Was Hygiene Like In The Victorian Era?

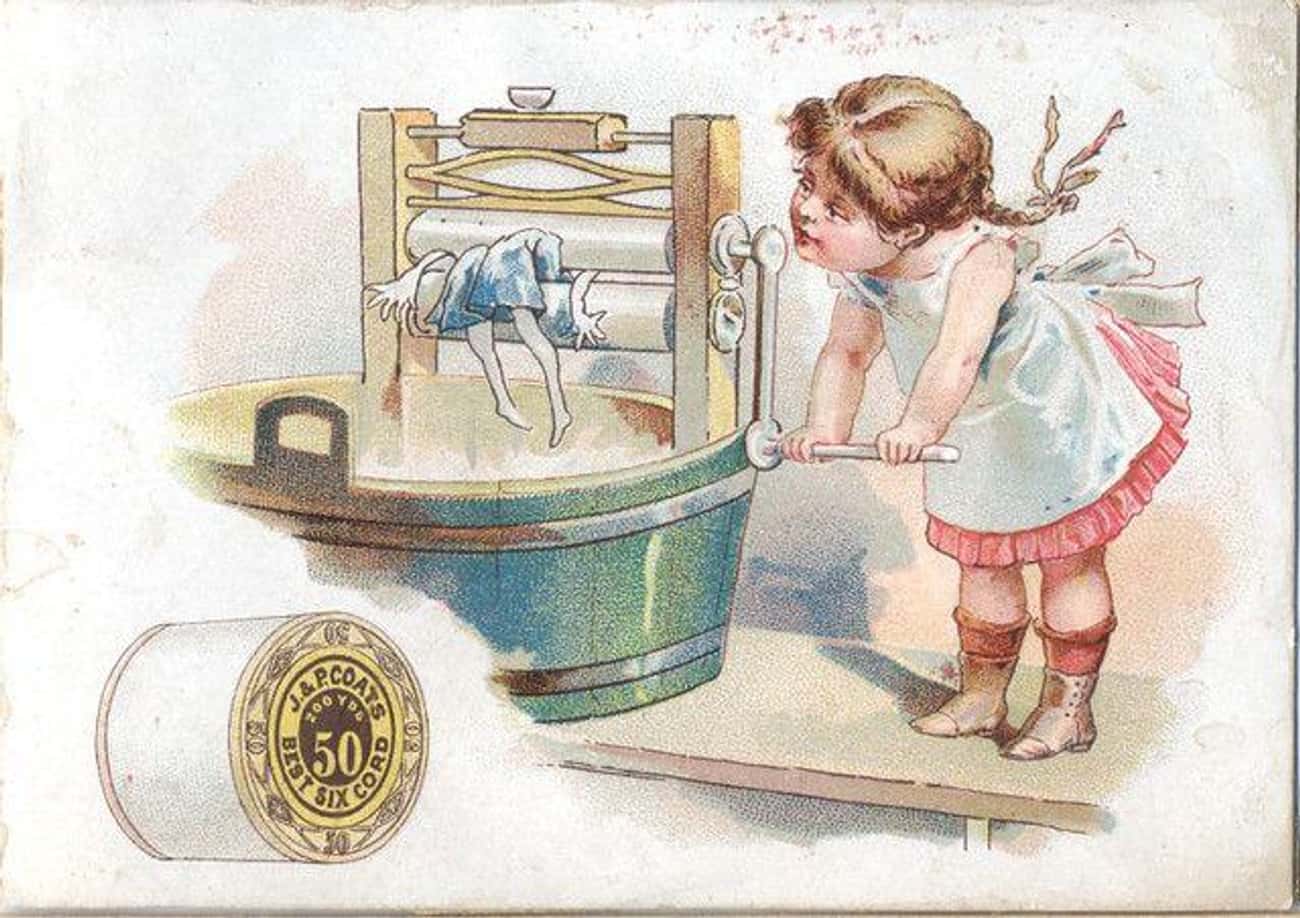

They Bleached Their Clothes With Urine

Where laundry was concerned, Victorians often used more than soap to "clean" their clothing. Grease and oil stains were regularly combated by rubbing chalk into clothing, while kerosene could remove grass stains and blood stains alike.

Milk was a go-to cleaner for removing urine stains and odors. In a similar vein, Victorians used their own urine to bleach clothes, since urine contains ammonia.

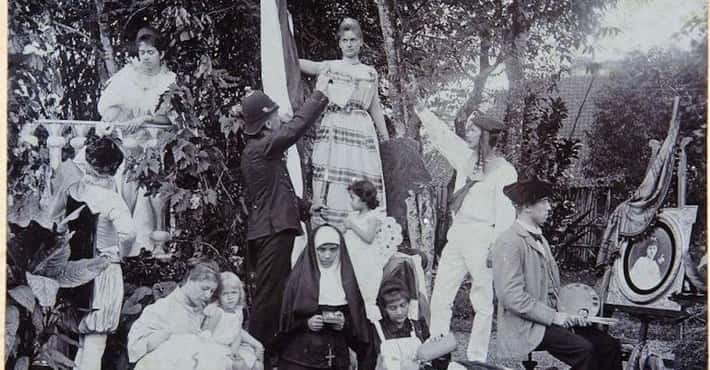

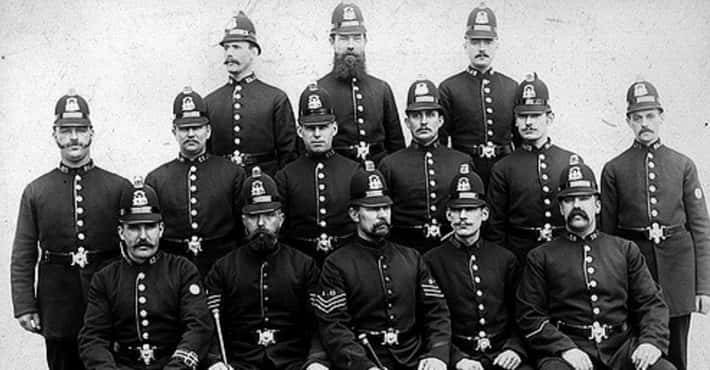

- Photo: Dupons Brüssel / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

They Made Homemade Toothpaste Out Of Cuttlefish

Middle- and upper-class Victorians could easily purchase toothbrushes and toothpaste, but most working-class folks had to make home concoctions. Makeshift toothpaste could be made at home using soot, chalk, or powdered cuttlefish, among other options.

Toothbrushes usually had harsh bristles and wooden handles. For those who could not afford a toothbrush, celery was thought to be abrasive enough to clean one's teeth while eating. While their oral hygiene wasn't ideal, their dentistry was even worse. Dental care was often provided by local barbers or blacksmiths if there was no dentist in the area.

They Had Indoor Toilets, But Not Indoor Plumbing

The first indoor toilets, or "water closets," were popular for their convenience, but since they predated indoor plumbing, waste often went directly into a large cesspool in the basement. While this seemed like an ideal alternative to outhouses or chamber pots, the cesspools eventually filled, and the smell often seeped into the house.

Thus arose the cottage industry of "night soil men," who emptied cesspools and sold the waste to farmers as fertilizer. Laws of the time stipulated that cesspools could only be emptied at night, as the task was "too disturbing" to undertake during the day.

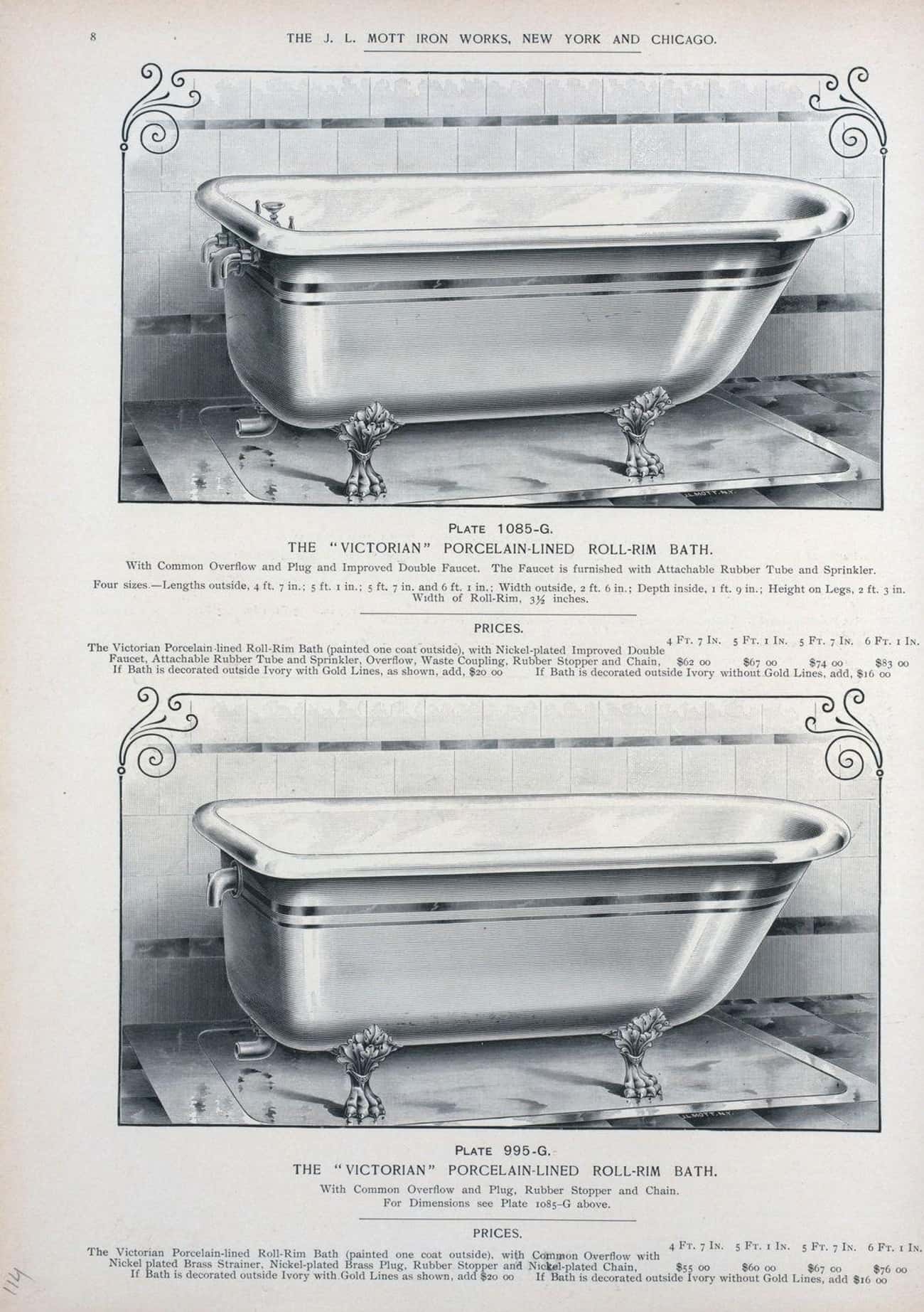

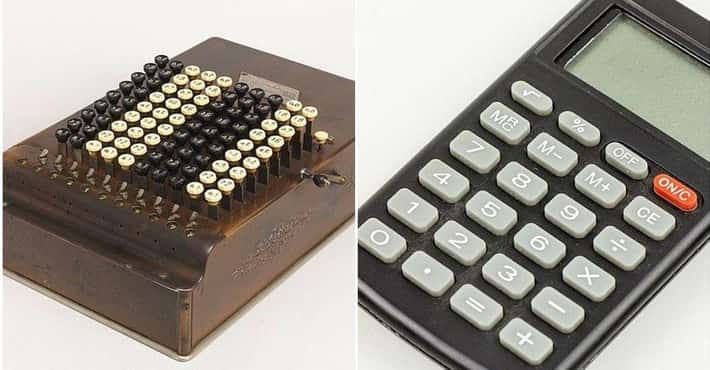

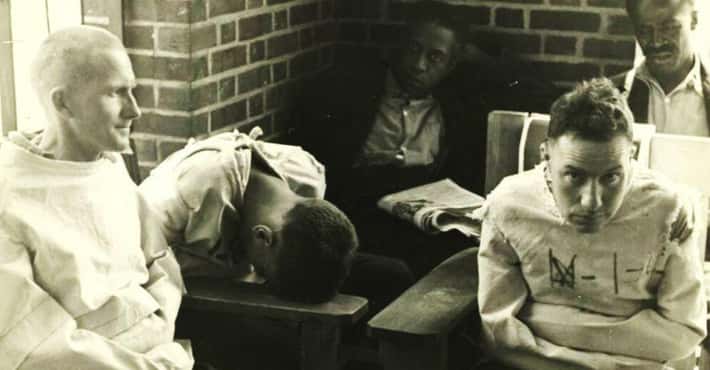

- Photo: New York Public Library / PICRYL / Public Domain

Books Instructed Them On How To Bathe Properly

As semi-regular bathing came into fashion, books were published that let Victorians know just what they could expect from a bath. One particular book offered various "Toilet Recipes" for curious, un-bathed Victorians. Much like the urban legend about swimming, people were advised against bathing within four hours of eating a large meal.

Victorians were also warned not to wash their faces when they traveled, unless they could purify the water with alcohol or ammonia beforehand. One of the more popular beauty regimens recommended a "Russian bath," which consisted of washing the face with extremely hot, then extremely cold water to help prevent wrinkles.

Vinegar And Eggs Were The Cutting Edge Of Hair Care

Victorians were obsessed with hair, but modern shampoo was a distant notion at the time. Women often broke several eggs over their heads, worked them into their hair, and then washed the egg out with a pitcher of water. Vinegar diluted with water was another popular option.

In fact, many cooking-related items were popular pre-shampoo alternatives. Rosemary, black tea, and rum were all considered perfectly normal as hair-washing substances.

- Photo: Wellcome Images / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 4.0

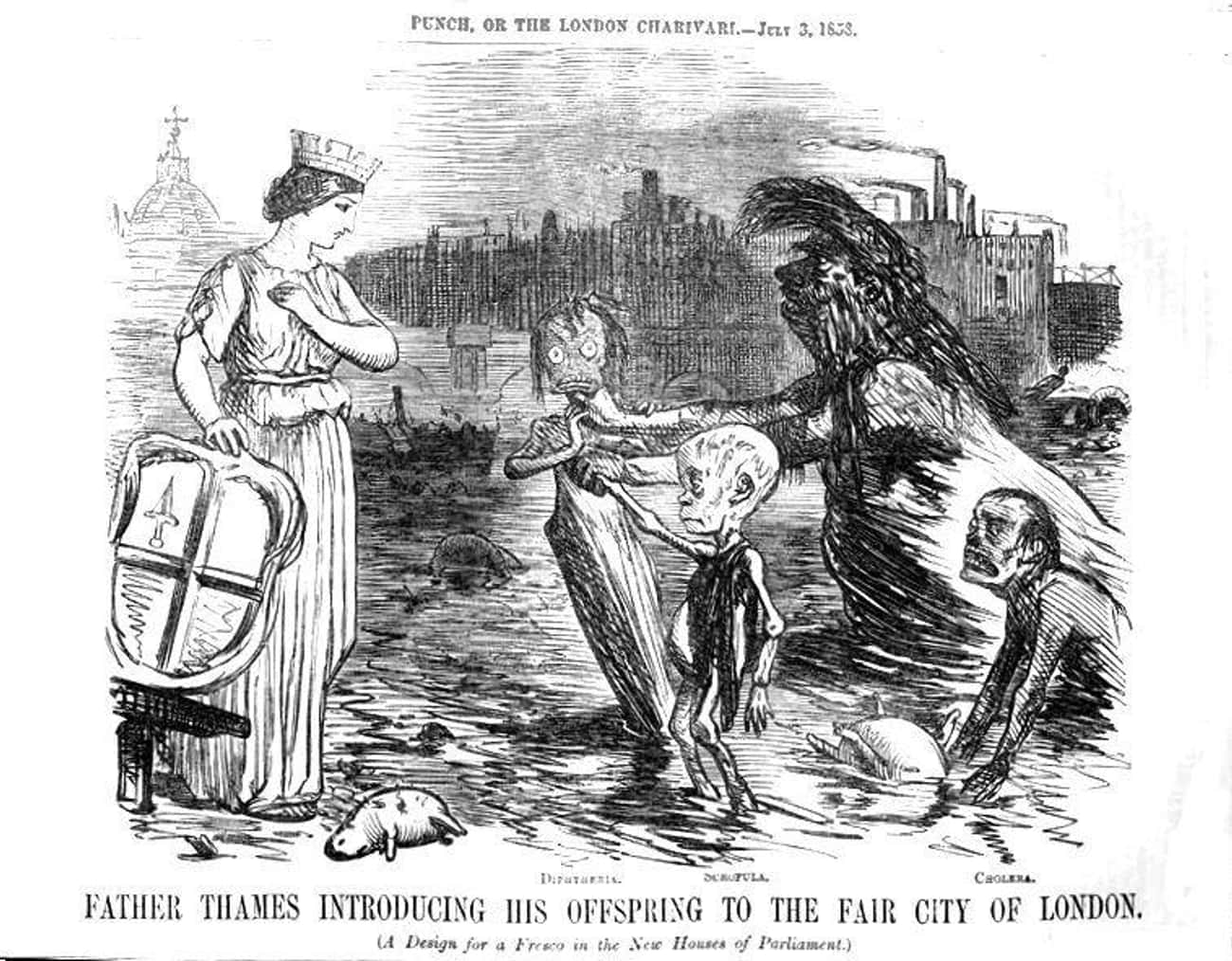

They Thought Bad Smells Were Responsible For Disease

Today, bad smells are considered unpleasant at most, but Victorians were convinced that foul odors were dangerous. The miasma theory, also known as "night air," claimed that a variety of conditions, including chlamydia and cholera, could be spread through unclean air.

Victorians went as far as to blame the poor health in London's impoverished areas on the smells emenating through the streets. Even famous nurse Florence Nightingale believed in miasma and thought clean air meant healthy patients.

In fact, the poor sanitation in industrial areas caused disease, which led to bad smells. Today, miasma is considered a false science in the medical community thanks to modern sanitation and medicine.

Women Used Military-Grade Bandages For Menstruation

Despite the many shortcomings of Victorian hygiene, the era marked the first time in history in which feminine hygiene was actually addressed in mainstream society. Disposable pads were invented in the late 19th century, and even an early version of the tampon was implemented around that time.

Women also found that bandages typically used for troops' wounds were useful for menstruation care due to their wood pulp base.

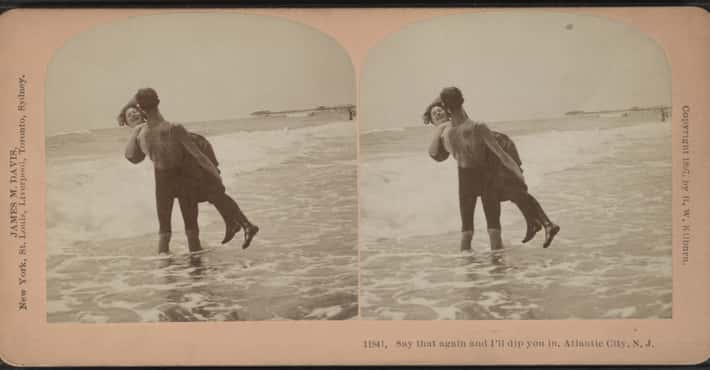

- Photo: Ewan ar Born / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

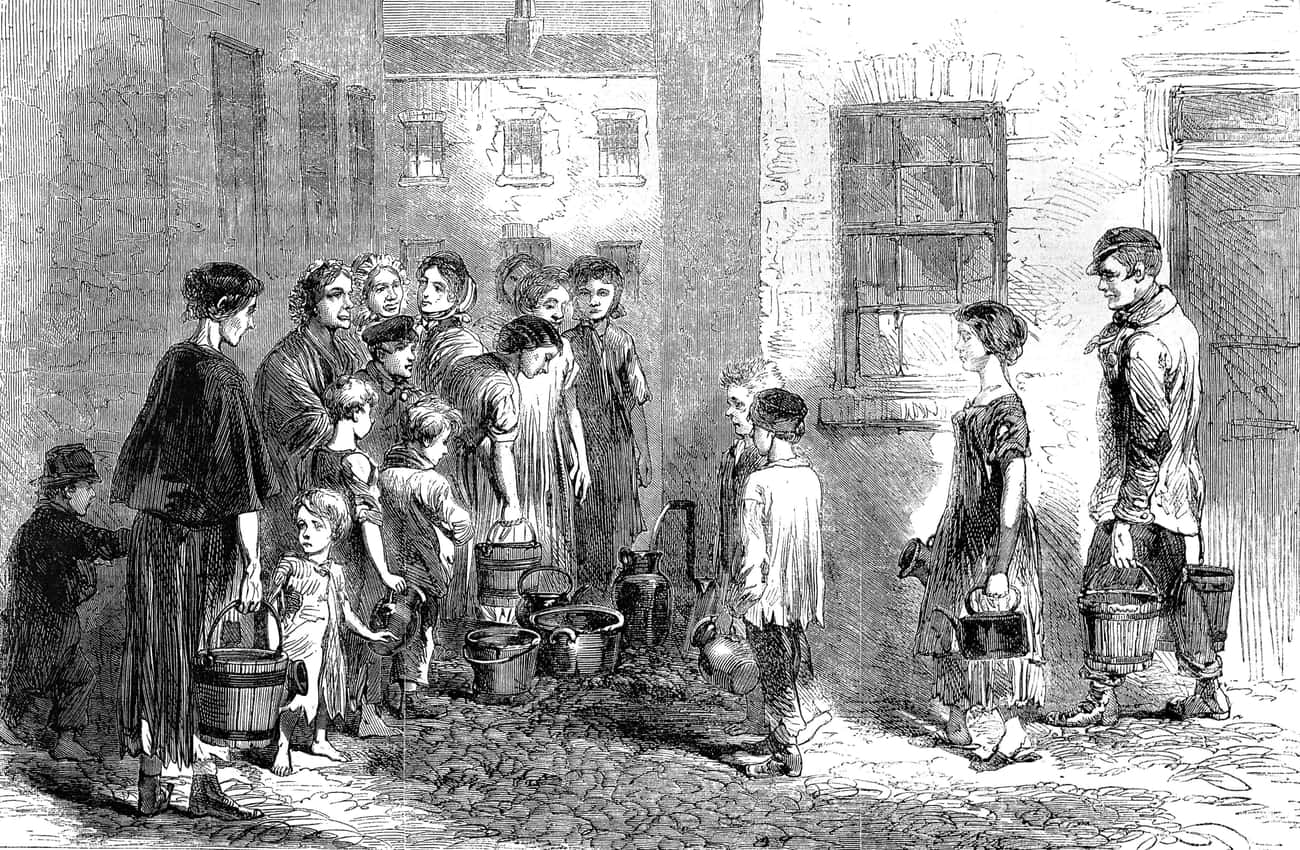

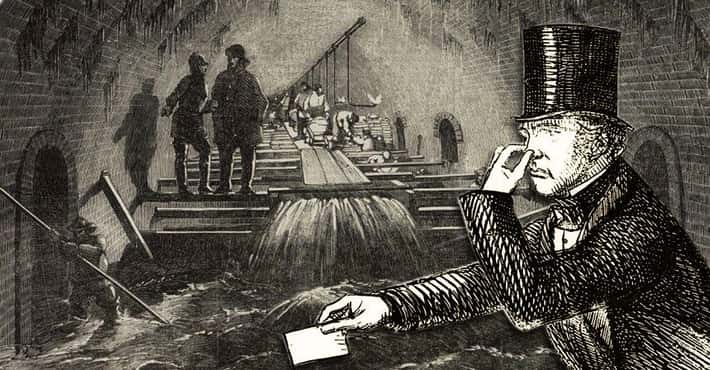

They Lived Through 'The Great Stink' Of 1858

Even modern cities may have a certain aroma during the heat of summer, but the stench emanating from London in 1858 shut the city down. The now picturesque River Thames was once the hub of the London sewage system, meaning citizens simply disposed of their waste in the river.

Londoners complained about the river's foul odors, and doctors cited the stench as the cause of rampant disease throughout the city. The summer of 1858 eventually became known as "The Great Stink."

Only when the winds from the River Thames blew towards Parliament did lawmakers take action. In a mere 18 days, a bill was passed that allowed for a modern sewage system in London.

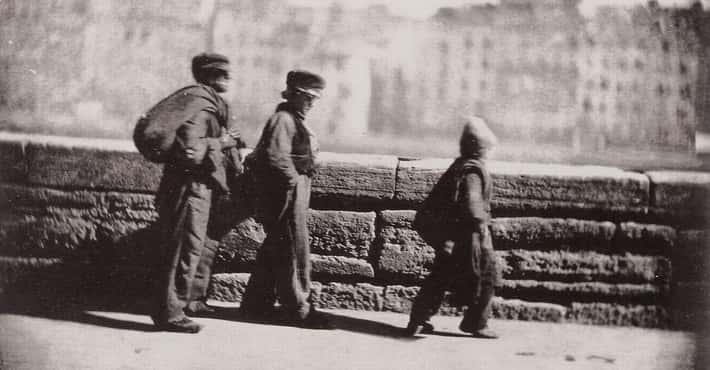

- Photo: Haabet / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

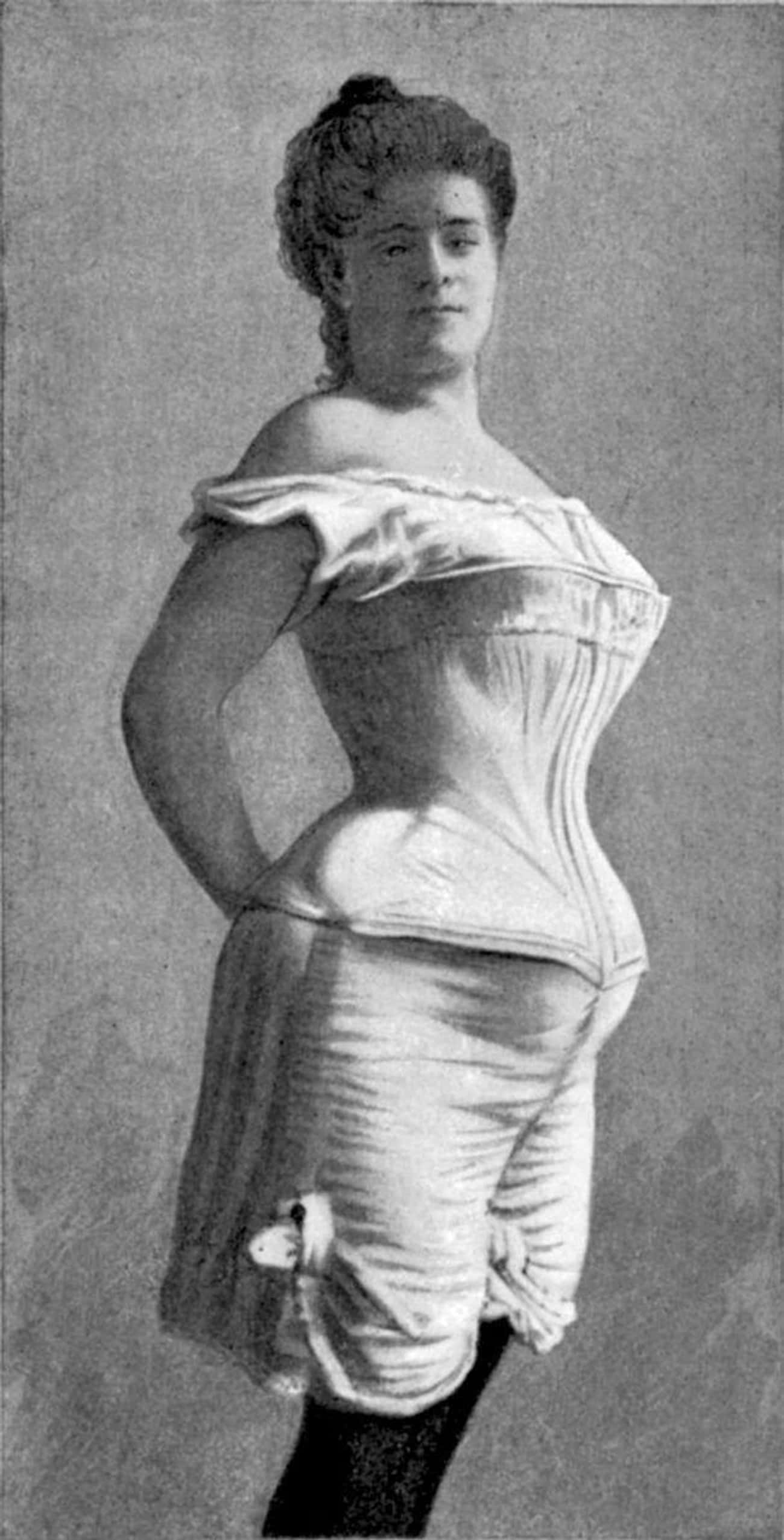

Long Skirts And Tight Corsets Were Blamed For The Spread Of Tuberculosis

In the Victorian era, women's clothing was blamed for tuberculosis and its spread. Doctors claimed that long skirts dragging in the street picked up the disease, causing women to unknowingly bring it into the home.

The tight corsets women were forced to wear were also thought responsible for tuberculosis, as corsets constricted the lungs. Higher skirts and looser corsets were implemented to help stop the spread of the disease.

Escort Work Was Outlawed To Prevent The Spread Of STDs

STDs were common in the Victorian era. Although considered socially unacceptable, escort work was a fairly common way for women to make a living in London's impoverished areas. Without easy access to contraceptives, these workers often transmitted STDs to their clients, who eventually transmitted them to their wives.

The spread of STDs eventually became a public health hazard and was addressed by the government. Women of the night could be detained and forcibly treated for STDs, though there were little to no consequences for their male clients.

Their Favorite Hair Care Product Was Full Of Lead

Hall's Vegetable Sicilian Hair Renewer quickly became a staple of Victorian hair care after it was introduced in the mid-1860s. Its main benefit was its supposed darkening properties that allowed people to maintain a youthful appearance.

Unfortuantely, Hall's hair renewer used lead as a bonding agent for other chemicals to help darken the hair. While the hair renewer did darken the hair, it was also extremely harmful. Hall's eventually lowered the amount of lead in their hair renewer and it managed to stay on the market into the 1930s.

- Photo: Britta Gustafson / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.0

They Used Listerine To Both Clean Their Floors And Cure STDs

While Listerine wasn't widely marketed until 1914, the mouthwash was invented by Dr. Jordan Lawrence and chemist-turned-entrepreneur Jordan Wheat Lambert in 1879. As Victorians slowly began to accept modern hygiene, Lambert initially experimented on marketing Listerine as a medical antiseptic. When his product failed to turn a profit, he began suggesting new and unusual uses for Listerine.

Listerine was marketed as a floor cleaner and a cure for both dandruff and gonorrhea before it was finally sold as a mouthwash. Gerald Barnes Lambert, the inventor's son, was responsible for this marketing decision and laying the foundation for the brand's century-long success.