When the artist Hans Haacke was asked to submit a proposal for a statue to occupy the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, his initial reaction was that it was a “good joke” to invite him but there was no way his work would be accepted. However, the project did appeal to him and he set about working up an idea for a 13ft-high sculpture of a horse skeleton cast in bronze, which would be finished off with a digital-display ribbon tied around a foreleg, like a bow on a present, which would show live prices from the London stock exchange. The work could be read in many ways, but few people would miss the implied critique of the relationships between power, money, art, privilege and history – the project, backed by the mayor of London, Boris Johnson, was to be sited outside the National Gallery during a period of unprecedented financial speculation in art.

“The reason I thought it would not be accepted was that I knew what would have happened in New York,” explains the 78-year-old German born artist, who has lived and worked in Manhattan for the last 50 years. “There is no way that something that plays with Wall Street in this fashion would ever be approved under the auspices of the mayor.”

So when it was announced just before Christmas that his sculpture, Gift Horse, would occupy the plinth for 18 months, Haacke declared himself “absolutely flabbergasted”. And he wasn’t the only one to be surprised. In one newspaper preview of the big arts events of 2015, the arrival of Gift Horse, which will be unveiled on 5 March, was compared to “letting Trotsky loose on Buckingham Palace” before the writer wondered: “Did Boris really give it the thumbs up?”

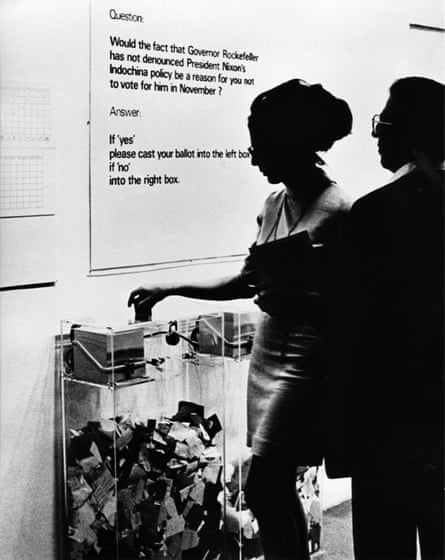

Johnson certainly sounded enthusiastic enough when he claimed that the work “encapsulates the dynamic mix of history and the contemporary that makes London such an exciting cultural capital”. He added that he was sure it “will get people talking”, which was a pretty safe bet as Haacke’s work has had no problem getting people talking since his 1970 Museum of Modern Art piece, MoMA Poll, embarrassed the re-election campaign of Governor Nelson Rockefeller – a leading MoMA donor and former museum president whose brother David was chairman at the time – in relation to the Vietnam war. (Haacke wasn’t invited back until the end of the 80s.) A year later, Haacke had a work about the business of a notorious New York slumlord banned by the Guggenheim museum on the grounds that he had “aims that lie beyond art”.

In the decades since, he has continued to draw attention to the often hidden connections behind society, politics, business and art, in work that has traced the Nazi background of prominent collectors and of the German Venice Biennale pavilion, and exposed the links between British Leyland and apartheid South Africa, as well as in projects that have criticised individuals – Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, Charles Saatchi, Senator Jesse Helms – and tobacco and oil companies with links to art institutions.

Nearly all of his work primarily draws on its location, and he says Gift Horse was always going to include some reference to the City of London as well as an oblique reference to Adam Smith’s “invisible hand of the market”. “Then the more I thought and learned about the space, including the fact that an equestrian statue was originally meant to be on the plinth” – of William IV, but the money ran out before it was completed in 1840 – “I wanted to do something with a horse. But to really speak about what is going on these days it had to be a skeleton and so I started to do some research.” He was directed towards George Stubbs’s 1766 book, The Anatomy of the Horse. “I knew Stubbs from the Tate gallery and other places, but I didn’t know he had dissected horses and made these engravings. That was a great revelation. And, of course, he is in the National Gallery with the painting Whistlejacket, and the work began to come together.”

Speaking at the Paula Cooper gallery in New York – where the showpiece in a well-received retrospective of his work last year was a characteristically pointed installation featuring billionaire David H Koch, donor to many rightwing causes as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art – Haacke shrugs when asked whether he is an American-German artist or a German-American. “But the plinth does seem to have clarified this a little,” he smiles. “I am the 10th artist to occupy it and until now it has been mostly UK artists with the second most popular country being Germany. However, apparently it is now being said that I am the first American to be on the plinth, even though the Goethe Institute puts me up when I come to London and has its logo on the poster. So there you are.”

Haacke, born in Cologne in 1936, first went to the US on a Fulbright scholarship in 1961. He cites two important moments in his education: first, when a high school teacher introduced him to art history – “I learned that art was not just a skill to render something, but it had deeper meanings” – and then when an art school tutor, Arnold Bode, who founded the five-yearly Documenta art festival, recruited him to work at the second festival in 1959. “There was a prominent display of abstract expressionism from America, but what was most important to me was seeing how things worked behind the scenes. That has proved very useful.”

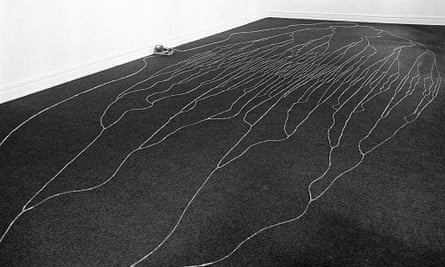

By the time he settled in the US, in 1965, he was an established artist working within a broad field that had recently been characterised as “systems art”, a system being, he once said, “a grouping of elements subject to a common plan and purpose that interact so as to arrive at a joint goal”. “The term was not my invention, but in the mid-60s I did adopt it as I felt that the terminology, and the conceptual framework, was in fact appropriate to understand what I was already doing.” Haacke’s best-known work from this period was Condensation, a clear cube in which the condensation cycle plays out in response to the ambient heat outside, but, he says, by the early 70s the term had become “contaminated by being used in terms of weapons systems during the Vietnam war. I didn’t want to be associated with that and so stopped using it, although I realise what I do now could be understood in terms of systems terminology.”

The dropping of the word coincided with more overtly political work such as Information at MoMA, which comprised a questionnaire asking visitors if they supported Governor Rockefeller’s stance on Vietnam. They didn’t. Haacke says if there was a eureka moment in moving his attentions from physical or biological systems towards social and political ones it came in 1968 when he was to deliver a speech about his work shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King. “That really got to me and so before I started talking about my work I gave a little preface tosay that whatever I say cannot take account of what happened to Martin Luther King and that was a gap I felt uncomfortable with.”

Soon after, as he observed the Paris student revolts and the protests against the Vietnam war, it became clear to him “that under the heading of systems are also social systems. And, as someone politically engaged, it would be strange if I did not expand in that direction, which I eventually did.” As he put it, he began to use the building blocks of social systems as materials in the same way a painter uses paint or a sculptor bronze in a distinctive body of work that has utilised paint, physical objects, text and photography, all underpinned by extensive research.

But the immediate result of goading Rockefeller was “to take me out of the system for a while”, he laughs. How much did he consider the repercussions for his career of taking on important art world figures and institutions? “I was naive. I thought that museums were, give or take, liberal institutions and, even though it rubs them the wrong way, they would not hold it against me. But I now take it for granted that there is a lot of self-censorship on the part of museum officials. And I can’t blame them. It is their job and why should they sacrifice themselves because of what I do. They say that they like my stuff, ‘but let someone else show it’.”

In career terms, he has also not made things easy for himself by refusing to be photographed by newspapers – “I have something against the fetishism of the artist that is associated with the face and celebrity” – and a deep scepticism about the art market. “I like to believe that when my generation put their feet on the ground, collectors bought works because they wanted to be associated with the art. Now it appears a great number of collectors treat it as an investment. That is disgusting. They have art advisers in the same way as they have financial advisers.” Haacke says the fact that he taught at art school for 35 years gave him a certain financial freedom, and he has instructed all the galleries he has been associated with that his work is not to be shown in art fairs. He also uses a contract developed in the 1970s that gives him 15% of any price increase when a work is resold. “It occasionally kills the deal. But I’m coming round to believe that the contract I insist on is a very useful litmus test as to who should, and who definitely should not, own my work.”

While his art deals with many of the issues that preoccupy him as a concerned citizen, he says there is no to-do list of causes for him to interrogate. “A work is usually more to do with the context, both in terms of the space in which something is put and the general social and political environment at the moment. I am a newspaper addict. The New York Times is my breakfast entertainment and so I do have a range of references to draw on. And sometimes my work has been criticised for being too much like journalism. But inevitably if you engage with the world and you respond to what is coming at you over the transom then it is a natural outcome.”

So how does he feel when a museum, or institution, or the fourth plinth committee, accepts his work? “Sometimes people think that thereby the whole thing is smothered, and doesn’t rub any more. But that’s not how I understand it. For better or worse, museums and institutions are the channel through which you can reach, even in a superficial way, very large audiences. And that can also be picked up by the press and others, and then it has a chance to become part of the public discourse. So in a very indirect way, you can play a part in shaping what people think and talk about and even who is going to be running the government. Not that politics is everything. And I have no delusions of grandeur. This is just one small stone in a large mosaic. But that one little stone? It really can change the colour and look of the whole mosaic.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion