He always wore a hat. Like everything else he touched, it became a totem drenched in personal meaning, the symbolic headgear of a self-appointed shaman. In reality, according to those who knew him, the hat covered scars from a Stuka crash, in which rear gunner Beuys was seriously wounded, on the eastern front in 1944.

That much is true. Probably. Yet the story Beuys later made up about his wartime experience has been discredited since his death in 1986 by people who bothered to check the Third Reich documents. Beuys claimed he was rescued, barely alive, from the burning Stuka by Tatar nomads and swathed in fat and felt to resurrect him. It was a tale that explained not just his survival but his rebirth as a radical visionary out of the ashes of his youth in the Nazi era. The trouble was, it was a lie. Does that matter? Is it still a useful fable, part of his crazy vision, or should we suspect that his entire artistic output is similarly dishonest, or even that it is tainted by a past he never truly rejected or explained?

It’s not as if you can escape the image of the burned Beuys saved by fat and felt in the Thaddeus Ropac Gallery’s ambitious survey of his art and ideas. These symbolic substances are everywhere. There’s a cello covered in grey felt, emblazoned with a red cross. Nearby hangs a felt suit in the same muted colour, as well as a camp bed swathed in felt. As for fat, here it is in the form of 41-year-old margarine in cardboard trays in a glass case. Take away Beuys’s myth and what does this stuff actually mean?

When I walked in and saw that felt suit, what I saw was despair. It has the look, to me, not of a shaman’s garb but the ersatz clothing of a totalitarian state. Far from escaping the past, the art of Beuys reenacts it. What about his “Feldbed”, or Campaign Bed – a day bed from his studio that he later turned into a sculpture? It is explicitly military, a camp bed from a long-ago war. But this exhibition made me fear I am giving Beuys the benefit of the doubt in seeing tragic depth in works that are glib symbols of redemption.

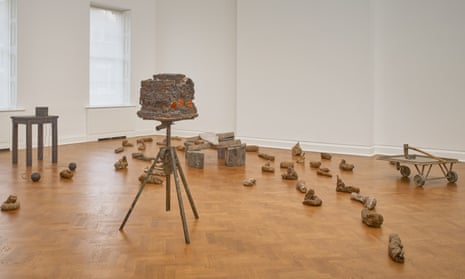

These are the meanings I prefer to see in Beuys’s art. With its old, worn and organic materials it has a loamy, disturbing taste of history. On a rusty tripod, for example, stands a dark cube of matted earth with smashed pieces of terracotta buried in it. This layer of broken pottery looks like the remains of an ancient civilisation. It is tremendously suggestive, an image of the archaeology of human life in all its violence and tragedy: the barbaric ages, the brief and vanished golden ages.

Thaddaeus Ropac – one of Europe’s top art dealers, who represents the Beuys estate – explains that this piece, Boothia Felix, symbolises a human. That arrangement of stones and an ironing board over there, that’s a stag. As for the turd-like excrescences of clay all over the ground, these are “lemmings” or “primordial animals”. All are components in Beuys’s Stag Monuments, a series of expansive installations he devised in 1982 out of the detritus of his studio. The biggest Stag Monument of all, with its lightning-like cascade of melted iron, is on permanent view at Tate Modern.

Listening to the gallerist, I am uncomfortably reminded of how I recently tried to explain Beuys to a group of Guardian readers at Tate Modern. Beuys movingly portrays the tragedy of modern history, I said – but then found it hard to explain just how he did. So perhaps my desire to see history in his art is just an attempt to rationalise the power it exerts on me.

Ropac’s exhibition suggests we really should take Beuys at his word. It draws on the Beuys estate to show how seriously he himself took all his mystic symbolism. In a group of early sculptures he made in the late 1940s, he portrays a suffering gothic Christ, makes a Celtic cross, and imitates an ice age Venus. He is reaching back for the roots of symbolism, the ancient mythic past. The most haunting of these works is an unfinished sculpture of a horse. He set out to make it using the ancient lost wax process – where molten metal is poured into a mould created with a wax model – but never got as far as casting it in bronze. Years later, at the very end of his life, he found this forgotten piece, split open the mould and put it in a vitrine. The wax horse is yellow, as if it were made of butter.

On a wall hangs Thor’s hammer, emanating curly bits of bronze. You can’t get much more Teutonic than that. Beuys may, after all, be an artist it’s best not to think about too much. He helped save European art after the second world war and inspires some of today’s most admired artists, such as Anselm Kiefer. Yet he was also a bullshitter, a fake prophet and a Wagnerian poseur whose overblown myths are as daft and empty as the Aryan nonsense he imbibed – without any choice – in his youth.

- At Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London, from 18 April until 16 June.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion