The Namazu-e Album at the Royal Ontario Museum and Its Online Exhibition

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, Canada, owns an accordion-style album containing eighty-seven woodblock prints depicting and satirizing social situations after a large earthquake hit the city of Edo (today’s Tokyo) in 1855. An online exhibition of this album, Aftershocks: Japanese Earthquake Prints, which displays a selection of forty-two prints, was launched on the ROM website in November 2022 and will be available for several years.

This kind of album (ori-hon) of earthquake-related prints—collectively called namazu-e, or catfish pictures—are not uncommon in Japan, but ROM’s album is unique in that it includes a preface written by a contemporary collector named Shuseidō Yūgi Dōjin (life dates unknown) two months after the earthquake. ROM acquired this rare album in 2000 from a local art dealer who specializes in Japanese art. The album has since been studied by researchers (Shiga, 2004), and it was exhibited at the ROM in 2009–10. This is the first time it has been made accessible to a worldwide audience as an online exhibition.

As I explain below, the creation and popularity of namazu-e were highly specific to the sociopolitical conditions in Edo in 1855. Nevertheless, the ways these prints depict the townspeople’s diverse reactions to the natural disaster and its aftermath—often in a humorous and satirical manner—has the potential to stimulate the interest and imagination of audiences today as well.

Album of Earthquake Prints, preface

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 55.4 x 35.7 cm (open)

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.2)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

What, then, are namazu-e? Generally speaking, they are printed works, including texts and illustrations, that were produced in response to several earthquakes that occurred throughout Japan in the late Edo period (1603–1868). More specifically, the term refers to those produced in great amounts right after the large earthquake in Edo in the tenth month of the second year of the Ansei era (in the Western calendar, November 1855). At that time, more than three hundred versions of such prints were produced quickly, without going through regular channels of official censorship, and they became instantly popular among the townspeople.

Why catfish? According to a common folk belief that prevailed throughout Japan by the late 17th century, earthquakes were caused by giant catfish who lived underground. These catfish were usually said to be controlled by the deity Kashima, who pinned them down with the kaname-ishi, or ‘foundation stone’, at Kashima Shrine, located in the province of Hitachi (today’s Ibaraki Prefecture). At the time of the Ansei earthquake, however, the deity was said to be absent, attending an annual meeting of major deities in Izumo, a region in western Japan. The catfish took advantage of his absence and shook off the stone, and its movements are what caused the earthquake.

The catfish in these prints, therefore, symbolize the earthquake. Interestingly, the roles they play are complex and various: they are monsters and troublemakers but also fortune-makers and even rescuers. The beneficial nature of the latter derived from the idea that a disastrous earthquake is meant to happen to realize a better society for people. According to this idea, ki—the vital energy of yin and yang—flows both in nature and the human body, and when the flow stagnates and yin and yang become unbalanced, people fall ill and natural disasters occur. Society and economy were understood in the same way: the stagnated flow of ki would cause an imbalance in the distribution of wealth, which would make society ‘sick’. Natural disasters in such times were thus understood as events that had to happen in order to cure this imbalance. Edo people’s belief in close connections among nature, humans, and society surely helped drive the wide popular reception of catfish prints.

Untitled (Kashima deity pinning down catfish with kaname-ishi)

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 25.1 x 37.2 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.48)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

In the early 19th century, the city of Edo witnessed rapid urbanization (the population is said to have risen to somewhere between 1 and 1.5 million by 1850), commercialization, and consumerism, which exacerbated the widening gap between the rich (feudal lords and wealthy merchants) and the poor (artisans, workmen, etc.). This inequality was compounded by the conventional social hierarchy that placed members of society in following order, starting from the top: warrior, farmer, artisan, merchant. The Ansei earthquake made the poor, who had already been suffering from social inequality, believe that the disaster occurred as a kind of remonstration of those at the top of the hierarchy and was meant to pave the way to realizing an ideal society for them. The unexpectedly improved economic situation for some of the poor after the earthquake—who received emergency relief and donations of money, rice, or accommodations from the government, feudal lords, and rich merchants, and also benefited from the reconstruction boom—were interpreted as a redistribution of wealth that signaled ‘the rectification of society (yo-naoshi)’. The reactions of the townspeople toward the earthquake and its consequences, as expressed in the catfish prints, are therefore diverse: not only fear, anger, and resentment but also joy, gratification, and happiness.

Many of the catfish prints are humorous and satirical, with multiple layers of parody and puns depicting the social conditions of the time, expressed through both illustration and text. Catfish prints became instantly and intensely popular thanks to the highly developed commercial print culture that already existed in Edo, which included books, pictures, and broadside prints (kawara-ban) distributed as a form of news media starting in the mid-18th century. Supporting this print culture was the relatively high literacy rate among Edo townspeople, said to be around 60 percent. Due to strict government censorship of printed matter, many prints and publications were filled with parodies, puns, and coded messages to get around the censors.

Untitled (Magic mallet of Daikoku, god of wealth)

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 35.6 x 26 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.3)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

Since the mid-1840s, the commercialization of the publishing industry was further accelerated by new, ambitious publishers who mass-produced books and prints of lesser quality. Writers and artists, too, were already producing satirical works filled with parodies and puns that mocked the social problems of the time. The creators of catfish prints—publishers, writers, and artists alike—took advantage of the chaotic post-earthquake situation and quickly found a business opportunity in the forced hiatus of the normal censorship procedures. The dynamic and humorous tone of many catfish prints was generated by the creative spirit of the makers, which, in turn, triggered the explosion of Edo people’s suppressed emotions.

Anthropomorphic depictions of both animate creatures and inanimate objects have been familiar elements of Japanese visual culture since ancient times. The anthropomorphic catfish’s lively actions in many catfish prints exemplify the natural affiliation of nature, humans, and society in Edo Japan. The multifaceted roles that catfish play in these prints—sometimes a monster, sometimes a rescuer, sometimes a subject of chastisement or of worship, sometimes simply a being enjoying itself—demonstrate the fascinatingly complex ways people related to the catfish and, by extension, to the earthquake itself.

People Who Gained (left) and People Who Lost (right)

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 24.9 x 37.2 cm and 25.1 x 36.6 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.44 and 2004.38.1.59)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

Catfish prints, created by and for Edo townspeople, also took on the subject of conflicts and contrasts between those who benefited from the earthquake and those who did not. The widening gap between these categories was a major point of interest, perhaps stemming from the sense of unfairness felt by the majority of people who did not receive benefits. The earthquake that was supposed to mend society for all had left them behind. This unfairness must have felt even more acute as those who earned extra income conspicuously spent their money in restaurants and pleasure districts. Catfish prints, which were meant to be a critique from below of the elite class, began criticizing those who had once been below as well.

The Ansei earthquake occurred during a time of intense colonization of non-Western countries by Western powers, an international situation that threatened Japanese independence. Japan had adopted a seclusion policy since 1639, with only limited trade with the Netherlands and China, but starting in the mid-19th century, Western countries tried to end this policy by repeatedly sending warships into Japanese waters. Two years before the 1855 earthquake, American steamships arriving near Edo stirred up tensions in the city. The sense that society was facing rectification thus surfaced from this preexisting social anxiety as well.

The fate of the catfish prints was, however, ironic. Unlike typical printed matter, the catfish prints were published by mostly anonymous artists and publishers operating outside the government censorship system. The government eventually banned their production, beginning two months after the earthquake. As the memory of the disaster began to fade and the reconstruction of the city progressed, the passion for catfish prints cooled—as did the transitory hope for social change. While similar prints were produced in the periods following subsequent large earthquakes throughout Japan, they did not earn the same degree of popularity as those produced in 1855. After 1868, when Japan underwent modernization, the medium of the woodblock print itself changed as well, and by the early twentieth century the production of catfish prints had come to an end.

Bird of Hardship

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 24.6 x 37.2 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.58)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

Dialogue Between Earthquake Catfish and Commodore Perry

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 36.4 x 25.2 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.78)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

As we have seen, the social context for catfish prints was highly specific to the sociopolitical situations of Edo in the mid-19th century. However, the online exhibition of catfish prints at the ROM reframes them from today’s perspective to emphasize their relevance to contemporary audiences. There are two main ideas for the audience to take away from the exhibition. The first is the way these catfish prints demonstrate how people and communities recovered from the complex emotional impacts and exacerbated social inequalities caused by a natural disaster, using a form of ‘social media’ that is more than 167 years old. Second, we encourage audiences to examine the underlying relationships between nature, humans, and society portrayed in these prints and become more aware of their own positions within the changing dynamics of these forces today.

The exhibition consists of three ‘stories’ that can be experienced in any order: Shaking Foundation, A Spectrum of Emotions, and A Fleeting Hope for Change. It is structured so that a viewer can start from any of the three stories and continue on to the others.

In Shaking Foundation, the focus is on prints that refer to a folk belief about earthquakes to explain the cause of the disaster, and the relationships among the three key elements of that folk belief—the catfish, the deity Kashima, and the kaname-ishi foundation stone. While most of the catfish prints are humorous and cartoon-like, some take a more journalistic point of view, serving as a source of information about the degree of the damage. The text in Figure 7 lists affected areas, the number of collapsed storehouses, and the location of the five official aid centres. The viewer can relate such prints to today’s news media and its coverage of similar disasters.

Untitled (Damage of the disaster)

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 51.8 x 37.4 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.32)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

Untitled (Edo catfish and Shinshu catfish)

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 50 x 36.1 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.35)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

A Spectrum of Emotions explores Edo townspeople’s diverse emotional reactions to the earthquake, as well as how a good sense of humour helped them cope with their suffering. Figure 9, for example, depicts four half-human catfish in formal kimono apologizing to a group of deities, which would have provided earthquake victims with a sincere apology that was impossible in reality. The online format allows viewers to zoom in on different parts of this print and access details. Similarly, Figure 8 illustrates people’s differing reactions to two giant catfish: some are angry and attack the catfish, while others try to stop them. Interestingly, their dialogue is written all over the image just as in modern comics. Here, as the viewer scrolls through, each person’s face is shown in close-up along with a translation of their dialogue. Such visitor experiences are possible only in the digital format, and we have taken full advantage of that.

Finally, A Fleeting Hope for Change discusses the social themes found in catfish prints. The prints shown here demonstrate Edo people’s more positive and hopeful reactions to the earthquake, derived from the belief—however fleeting—that the earthquake was meant to happen and would mend their ‘sick’ society. In Figure 10, the catfish are interpreted as rescuers of people buried under the wreckage after the earthquake—a visual metaphor for the failing social system and crushing economic inequality. In a parody of a treasure boat, those who have gained from the disaster replace the Seven Gods of Happiness on a catfish boat floating on fallen roof tiles. Optimism prevails and people are happy, while the wealthy are satirized as sick people excreting money for artisans. At the same time, social tensions are also depicted in the prints; the widening economic gaps between social strata and broader international political issues are not ignored.

Untitled (Funny ensemble of people)

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 24.8 x 37.5 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.6)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

Mercy of Social-Mending Catfish

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 23.6 x 36.7 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.84)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

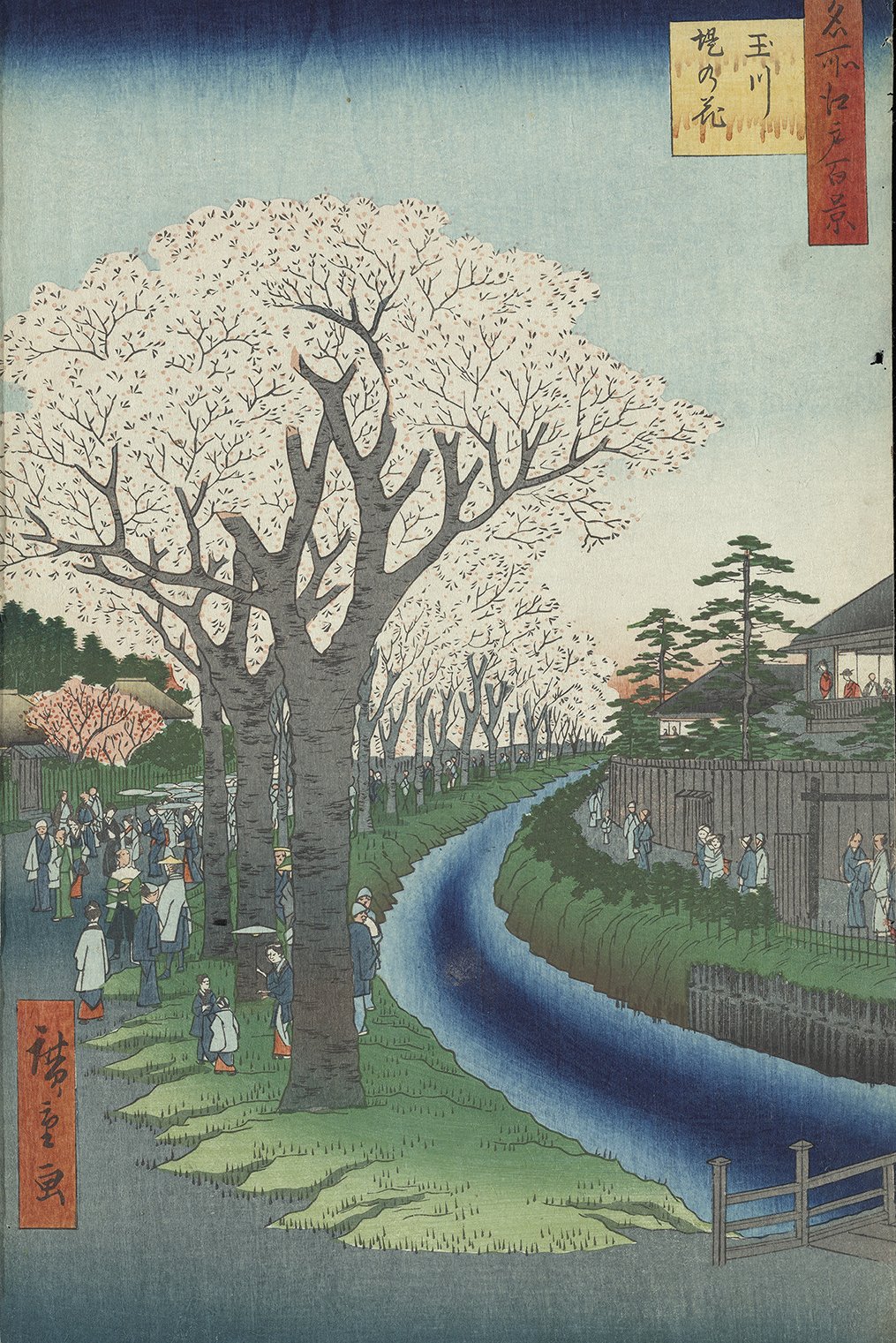

Each story ends with the same print, which is not a catfish print but rather Utagawa Hiroshige’s Cherry Blossoms on the Banks of the Tama River from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. This print was made only four months after the earthquake, but it shows a very different view of the city of Edo, suggesting the short-lived nature of the catfish prints.

Throughout the exhibition, a variety of digital experiences are designed to provoke viewers’ interest. Details of the prints appear in close-up as the viewer scrolls through them—an experience that is hard to achieve in a physical exhibition. Also, taking advantage of the fact that ROM has a fish curator, a short video of Nathan Lujan (a specialist on catfish) discussing a Japanese catfish specimen from the ROM’s collection is part of the story Shaking Foundation, allowing the viewer to compare woodblock print images of catfish with the actual fish. The viewer can also explore an interactive 3D model of the specimen.

Additionally, short videos by three experts in related fields—environmental justice, disaster management, and Edo social history—are incorporated throughout the exhibition to expand the viewer’s interest and knowledge. In Shaking Foundation, Kristen Boss, Assistant Professor of Indigenous Science and Technology Studies at the University of Toronto, Mississauga, and Co-Director of the Technoscience Research Unit, speaks about environmental violence and justice from the Indigenous perspective. In A Fleeting Hope for Change, Jazmin Scarlett, a social volcanologist, speaks about disaster management and how people live in environments with natural hazards. Gregory Smits, Professor of History and Asian Studies at Pennsylvania State University, speaks about the history of earthquakes and catfish prints as well as the political economy of post-earthquake Edo.

Due to their complex enmeshment in the historical, cultural, and visual vernacular of their time, catfish prints have not drawn major attention outside scholarly circles of specialists until recently. We hope that this online exhibition will invite a broader public to explore the humorous yet deeply meaningful world of catfish prints. In an age of social media and increasing natural disasters around the world, the role these prints played in the aftermath of an earthquake in Edo Japan can be more meaningfully appreciated than ever.

Rich is Less Rich, Artisan is Richer

Japan, Edo period (1603-1868), 1855-56

Colour woodblock print; 24.9 x 37.4 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (2004.38.1.18)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

Cherry Blossoms on the Banks of the Tama River, no. 42 from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo

By Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858); Edo period (1603-1868), 1856-59

Woodblock print on paper; 33.3 x 22 cm

Royal Ontario Museum (973x57.18.34)

Courtesy of ROM (Royal Ontario Museum), Toronto, Canada. ©ROM

Acknowledgements

The content and structure of this exhibition were the product of a close collaboration between ROM’s interpretive planner, Kendra Campbell, and myself. I greatly appreciate Kendra’s versatility, creativity, and thoughtfulness, which were essential to making this exhibition possible.

Akiko Takesue is Bishop White Committee Associate Curator of Japanese Art and Culture at the Royal Ontario Museum.

Selected Bibliography

National Museum of Japanese History, ed., Namazu-e no imagineshon, Sakura, 2021.

Hidemi Shiga, ‘The Catfish Underground: Japan’s Earthquake Folklore and Popular Responses to Disaster’, Orientations 37, no. 3 (April 2006): 77–80.

—, 'Study of the Ansei Edo Earthquake Wood-Block Prints in the Royal Ontario Museum’, MA thesis, University of Toronto, 2004.

Gregory Smits, Seismic Japan: The Long History and Continuing Legacy of the Ansei Edo Earthquake, Honolulu, 2013.

Noboru Miyata, ed., Namazu-e: Shinsai to nihon bunka, Tokyo, 1995.

Explore the exhibition on the Royal Ontario Museum website here.

This article first featured in our January/ February 2023 print issue. To read more, purchase the full issue here.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.